You have no items in your shopping cart.

Chan Chu

Most excellent toad!

Barbara Stacy

A THREE-LEGGED TOAD crouching on a pile of gold is not, to put it as kindly as possible, a winsome sight. Yet the Chinese hold such an icon in high esteem, for it represents Chan Chu, the god of prosperity. The fat-bellied image, sometimes conceived as toad, sometimes as frog, engages in double duty. He encourages money to enter the home and also wards off, guarding existing wealth. His nostrils flare and his red stone eyes glitter, offering a vaguely threatening aspect to deter thieves. From his massive jaws a square-notched gold coin dangles, decorated with a dragon and bird. The coin calls out to other coins, come in, come in. Tasseled threads anchored with more coins may hang from his mouth. The circular symbols of all things, yin and yang, crown his head. Seven stones matching his eyes are set down his back in the form of Ursa Minor. Chan Chu generally sits facing the door, the better to welcome good fortune as it dances in. According to feng shui masters the image is best placed in a corner, best for chi energy. Alternatively the toad may oversee a computer used for business or a work station with account books. At night the householder may reverse the idol to keep watch indoors, on duty so that wealth will not vacate the premises. The amphibian divinity also turns up in Chinese shops all over the world, on shelf or counter, taking care of business.

The Moon Connection

Legend has it that Chan Chu is sometimes seen at the full moon where good fortune is about to descend. His lunar aspect is symbolized by the seven-star constellation and the leg deficit, three legs numbering the same as phases of the moon. According to myth, Chan Chu is an aspect of the dazzling moon goddess Chang-e. She was the wife of Hou Yi, a supernatural archer who had received an elixir of immortality from Hsi Wang Mu, the Queen Mother of Western Paradise (see WA 08/09). The substance was a gift to help Hou Yi forever guard mortals against cosmic problems. Chang-e didn’t care diddley for cosmic problems. So what? She, the most gorgeous woman in the world, deserved immortality more than anyone. The arrogant Chang-e grabbed the elixir, clutched it to her bosom and fled to the moon. The Queen Mother of the West, enraged at the theft, turned Chang-e into what may be the polar opposite of human beauty – a toad. And there she lives on in the story as a lumpy amphibian, forever doomed to mix and remix the ultimate remedy – the elixir of eternal life.

Whoosh!

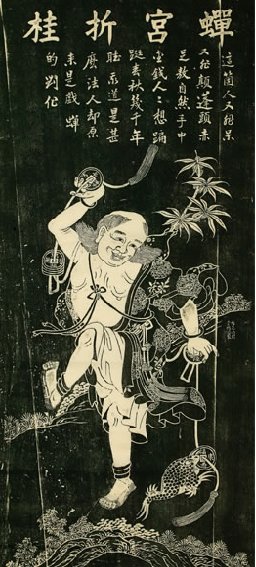

A parallel myth. The toad is the pet of Liu Hai, a Taoist sorcerer and alchemist. Chan Chu serves as a living magical carpet. He flies Liu Hai here, there, and everywhere in the world – or as far as we know, in the galaxy or in the past or in the future. But the companions have a problem. While most toads are landlubbers, some enjoy spa pleasures, little hydrous vacations from time to time. When the need for R and R strikes Chan Chu, he hides from his old friend in deep wells. He can only be coaxed out with shiny gold coins, which Liu Hai dangles on knotted threads. Chan Chu bites, Liu Hai hauls up, and they proceed on their usual skyway roaming. Icons of the immortal companions are found in Chinese shops everywhere. Liu Hai balances on the back of the huge toad, belly correspondingly fat, juggling gold coins, radiating cheer, enjoying his spooky travels and do-good work. In modern China, long secular, newly powerful, it is difficult to know how many people still honor old idols. But Chan Chu and his flight passenger are still popular as lucky talismans. They range in size from key-chain ornaments to the height of toddlers, in materials from glowing jade to the base metals familiar to the tenth-century alchemist Liu Hai.

One Toad, Two Good Stories

Both myths, lunar and aerial, may derive from ancient beliefs about the Bufo clan, earth dwellers since dinosaurs shook the ground. Medicinally “toad grease” from the skin was applied to infected wounds and rashes. Certain extracts served as potent painkillers, others form “stones” as aphrodisiacs. Each May local Dragon Boat Races take place to discourage diseases that come with hot weather. Celebrants call on the traditional “five poisons” to aid in pestilence protection -- scorpion, spider, snake, bee and toad. The hoppers and leapers are also symbols of longevity, as are pines, peaches, bottle gourds, and certain mushrooms. Some toxins in toads behave themselves like hallucinogens, offering vivid sensations of flight. The alert reader, or even the reader that may have dozed, will note that the two myths are contradictory. Either our toad is on the moon plying mortar and pestle or he is the splendid steed of Liu Hai. Enjoy both impossibilities that deviate from the confines of reality. The more preposterous the stories, the more we delight in them.